You Can Copy your Product — But Should you Paste it into Other Markets?

Localization isn't a "nice to have," but is business critical when expanding to new markets.

Hi Nimble UX Readers,

It’s been a while. Q1 2024 was busy for Velocity Ave. On the writing front, I’ve been collaborating with a few UX leaders on some exciting topics. I’m thrilled today to share one of those pieces, co-written with my friend and colleague . Ted is a global ethnographic researcher with 10+ years interviewing individuals about their technology use around the globe, in both academia and with Google. Ted writes a weekly newsletter, co-hosts a podcast, and is humble as can be.

We’re sharing v1 of a framework here that we hope sparks conversation, thoughtful consideration, and ultimately increases research investments.

Shout out to our early readers and editors, it takes a village. We appreciate you, Risha Lee, Shima Houshyar, Kaelyn Quinn and Emma Roach.

Thanks for subscribing, sharing, and engaging.

Warmest,

Maya

A globetrotting product has allure, mystique, and a story to tell beyond market saturation. Starting in the 1990s the promise of international growth expanded the concept of Product-Market Fit to Global-Market Fit. Now thirty years later, it’s more important than ever to consider markets outside the U.S. and Europe: analysts estimate one billion people will join the global marketplace in the next seven years. Much of this growth will occur in India and China, but also countries long ignored by global organizations, including Indonesia, Bangladesh, Vietnam, Brazil, Nigeria, Turkey, and Mexico.

Expansion seemed as simple as an Austin Powers operation, but many teams found that moving abroad garnered minimal Return on Assets (ROA). So began an appreciation for localization. Initially focused exclusively on language and other small changes, localization now encompasses an understanding that products must evolve to fit new market needs.

If you’ve been a bystander within a company copy-pasting their way into international markets, we hope to empower a better approach.

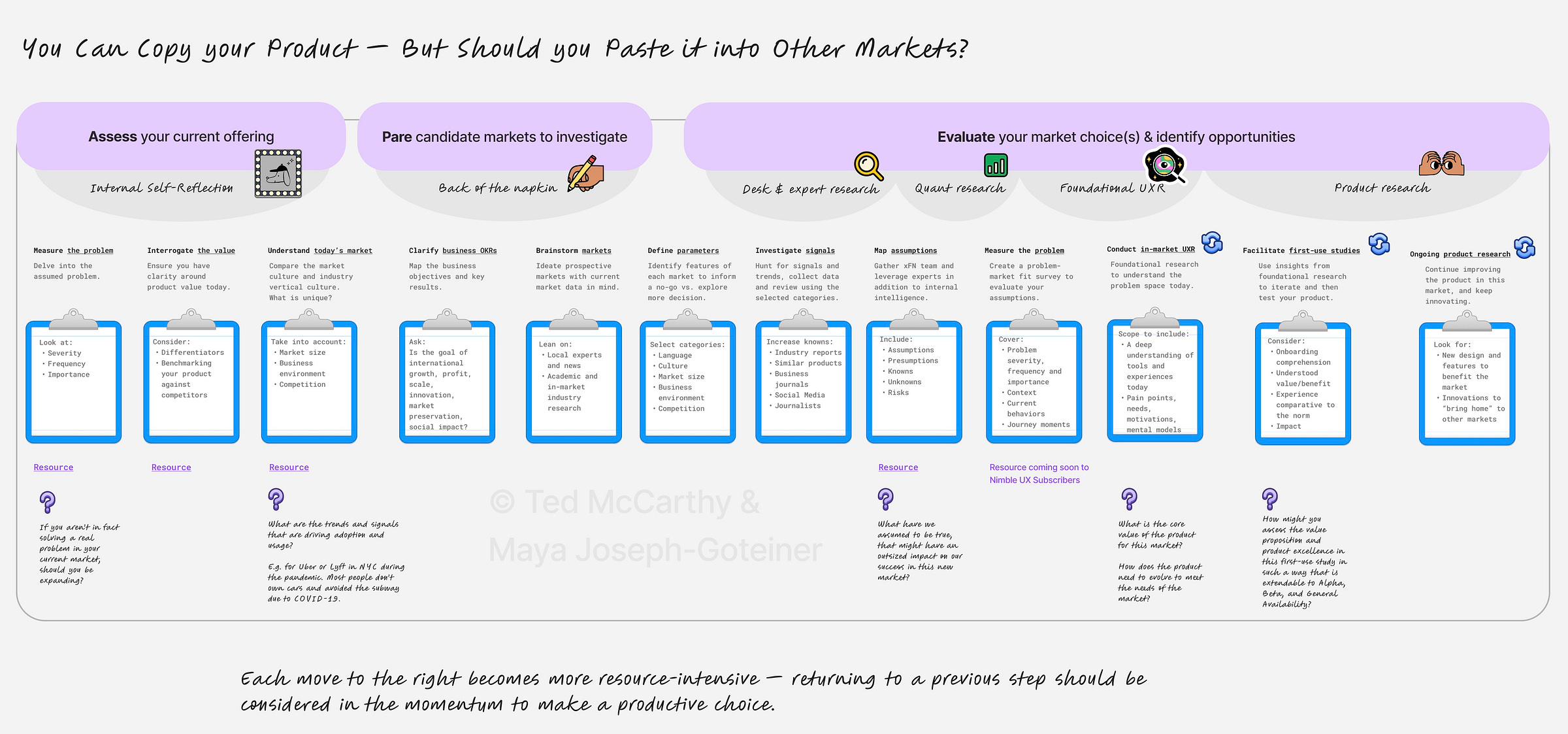

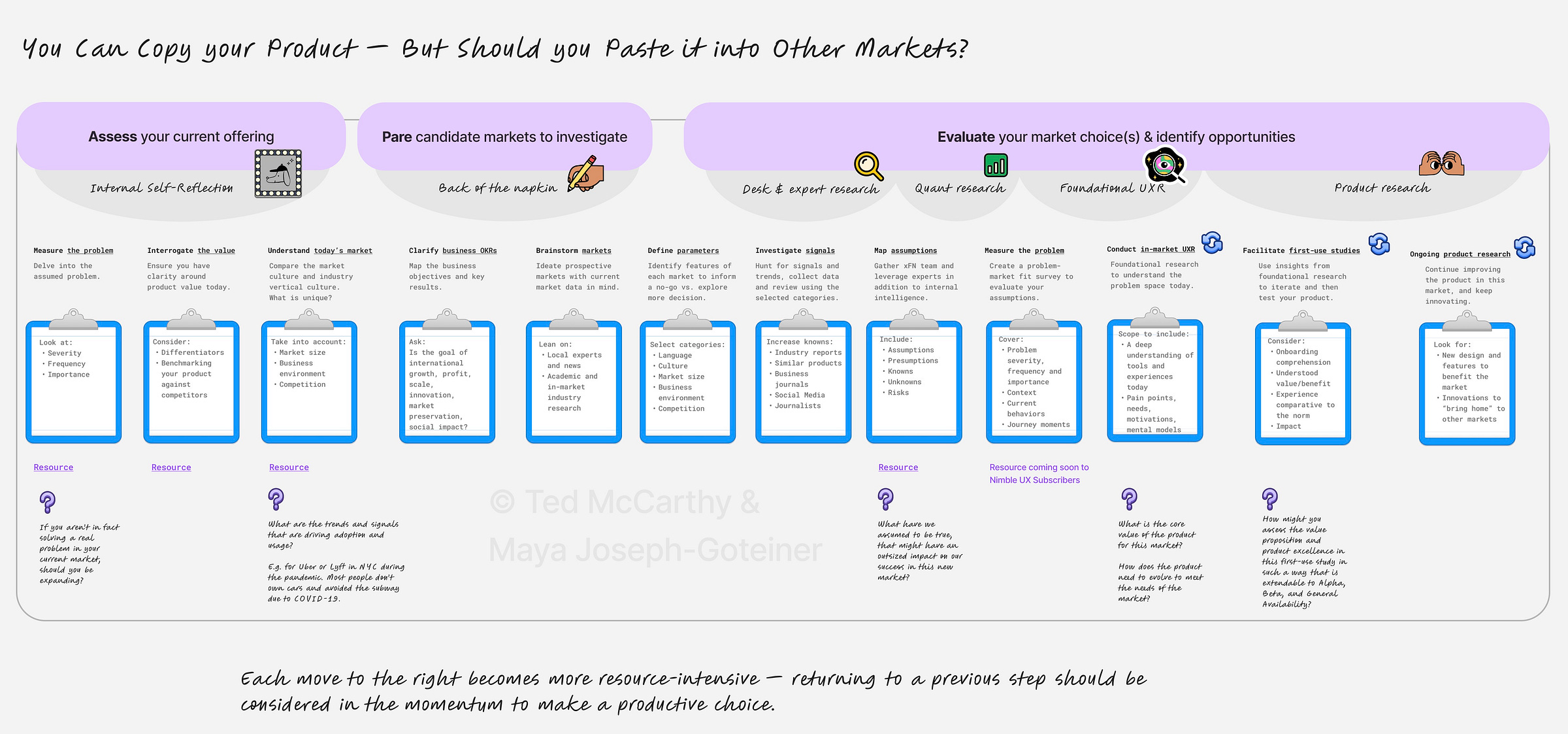

We have a framework to support challenging the status quo. It’s designed to lead companies to identify candidate markets for expansion, root solutions in a problem and develop features that are localized.

We explain how:

We must consider localization through multiple lenses, including: existing systems, social structures, cultures, tech and business infrastructure.

There’s no proxy for localization — it requires in-market research. The more you invest upfront, the more you save in product, engineering and marketing resources. And the more likely you’ll see long-term success.

Much like initial product development, localization is a non-linear, iterative process. Your product will and should change based on research learnings.

There’s No Blueprint for International Expansion

We all preach ‘know who you’re designing for’ as the elemental question, even after initial market success. Yet too often when expanding internationally, companies take their past success building in one place as a blueprint they can replicate — without considering how 'who they are building for' has fundamentally changed.

Despite the UX industry’s maturation, researchers run into a lack of human-first frameworks to guide market expansion. In our experience, large public companies often approach global expansion by pairing a quantitative assessment with a “Design for Everyone” lens, one that overlooks the nuanced needs of new markets. While “copy-pasting” past successes requires minimal upfront resources and effort, the risk of long-term failure is high.

We can find examples of localization successes and failures in a variety of industries. McDonald’s famously achieved international success by changing menu items to agree with local appetites and cultural expectations. But Home Depot struggled to expand in China, a failure some attribute to the country’s short history of home ownership, and minimal space to store purchased tools in most homes. These and other factors fundamentally challenged the company’s business model, making localization unattainably costly.

Modern technology companies aren’t guaranteed international success either, even with the capacity of advanced analytics. Netflix has seen great success taking localization to new levels, working with local writers and actors to produce novel content appealing to local entertainment appetites. Uber, on the other hand, delayed cash payments in cash-heavy South Asia, thus ceding market share to local players like Grab — which now claims over 70% of the rideshare market in the fast-growing region.

Uber, at least, seems to have learned from its localization failings. The company now offers motorbikes, boats, tuk-tuks, and even helicopters in various markets to accommodate the service to local transportation needs.

From Marketing Theories to Real-Time Feedback

There’s no shortage of approaches businesses can leverage when hoping to go global, including market segmentation, target market, positioning, diffusion of innovation, and customer-centricity. These techniques and theories however emerged from the discipline of marketing at a time when there were few tools to capture live customer feedback. They aimed to maximize business expansion, agnostic of problems or needs, optimistically setting a company in a new direction.

As analytics and research have become mainstream, investments have shifted. Barriers can seem even lower today with real-time assessments of market success, but many have forgotten in this momentum that localization isn’t just important — it’s critical.

Movements like “fail fast” dramatically lower standards, encouraging product teams to float down the lazy river of product development, and feel they can skip user research to “learn on the fly” in new markets.

There’s a better way.

Developing a Human-First Framework

While businesses in theory can expand everywhere, should they? We believe it’s possible to lower risk in assessing global expansion with the elements of niche.

Just because Country X is next door to Country Y or executives assume the culture is similar, these are not indicators of an “analogous market.” Product-Market Fit seeks to define the problems, values, and benefits for people. Not only the product, but also the market in which it operates.

Designing for a market requires deep understanding of a locality — its cultural norms, social structures, power systems, and institutions.

A market’s uniqueness does not center on technology or demographics, but rather human experiences informed by perspectives, challenges, needs, and desires.

Bringing Innovation “Back Home”

Though some may fear prioritizing research in new markets will detract from existing product experiences, learnings can frequently be transferred across geographies. Building a solution for one group of customers can improve the experience bar none.

Google’s Files team, for instance, used research to identify a specific problem for Indian phone users — data-heavy “Good Morning Messages” devouring scarce phone storage — then worked to build an innovative solution to solve it. This solution not only launched the product to viral success in India, but also opened the door to create other novel, valuable features for U.S. users.

Similarly, WhatsApp optimized product design to function well on poor networks in emerging markets — a factor that surely contributed to its 2.7 billion users today. Many WhatsApp users live in places where mobile data is expensive and sparse, where these considerations provide great value. But even New Yorkers and Londoners can enjoy WhatsApp’s attention to poor network conditions when they lose cell service on a subway or plane.

“Curb cutting” is a term borrowed from the accessibility community to describe this idea, and refers to sidewalk indentations on street corners built to help individuals with mobility limitations move between the sidewalk and street. But these “curb cuts” help others, too — such as small children, animals, and people with bicycles, trashcans, and rolling suitcases.

While we must attend to the needs and preferences of our target markets, doing so exclusively hampers our ability to solve hidden problems. A short-term lack of internet may seem a small obstacle for New Yorkers on the morning subway, but a tremendous one for others.

By striving to understand problems where they’re most acute, we can focus our energies on solving them to improve the product experience at large.

Choosing Where (and If) to Go Global

When talking about market expansion, consider these phases:

1. Understand your current offering.

Before expanding internationally, consider: are you sufficiently addressing human needs in your primary market? Are there new, fruitful arenas for product innovation? What about your current market and your product’s vertical have allowed for success — do these conditions exist elsewhere?

2. Pressure test the problem.

If you have already found Product Fit in one market, then you are likely solving something contextually important. In an ideal world, you have benchmark data in your current market around the problem specificity, severity, frequency, importance and product-related data about the value you generate. We define these terms in Nimble UX’s prior post “Don’t Design for Everyone, Design for Niche”. Without this data, you won’t be able to compare new markets and find people with contexts where similar problems are significant.

3. Assess if the new market is a likely candidate for product success.

When paring candidate markets to investigate in detail, speak to local experts and invest in desk research to select a few candidate markets for expansion. It’s important at this stage to assess the goals of expansion — increasing profit; growing customer, user scale, or social impact; discovering innovations; or something else? What markets seem amenable to these goals, given market size, ease of doing business, language and industry culture similarity?

As discussed, Home Depot failed to succeed in the Chinese consumer market due to a number of deep, abiding cultural factors. While the company could have changed to fit the market, would it have been worthwhile? Such changes may have fundamentally required a rethinking of its entire business model and identity. Though not impossible, Home Depot should have prioritized entry into other markets requiring smaller “localizing” alterations.

4. Evaluate your market choice(s).

In-depth research begins here — ideally involving local expertise. For each of the candidate markets, conduct some combination of market research, a survey to assess problem-market fit, and foundational user research. Finally, detailed product research can validate the product serves local market needs, and help discover new features and designs to accommodate and solve them.

5. Identify how the product should change to better fit the new market(s)

While the term localization can connote mere product language changes, it should include far more. As with the example of Uber delaying the acceptance of cash payments in cash-heavy south Asia — and thus ceding a great share of market success to local players — entirely new product features and capabilities, ideally driven by expert and in-market research, may be necessary for success.

Continue researching the product in the new market(s) to improve it for that specific place. But don’t stop there: continue assessing which innovations improve the experience or value for existing populations elsewhere.

Does all this sound daunting? Lucky you — we’re here to help.

Take a look at the detailed framework, and reach out to Ted or Maya on LinkedIn if you want to chat.