In 2019, I stood in front of a group of 71 people at a Google event and said “now we will die.”

Although my choice of words was stark, maybe cultish, and insensitive out-of-context, I was the facilitator. I was about to introduce the next exercise, a Eulogy, at the Future of Ads Co-Laboratory. I needed to quiet the room and get the attention of participants. Goodness did it work.

“Death” isn’t a word frequently spoken in big tech, but it’s a common fate for products. We’ve just adopted a less animate descriptor, to “Sunset,” when a product is shut down. For startups that go bust, we aren’t as genteel, instead labeling them “Failed”. What unites these two product development events however, is surprisingly akin to the common human reaction to death - erasure and omission. As in life, in these product development environments, we scarcely talk about the potential of death.

When death shows up “too late”

There are outliers. In some company cultures post-mortems are common practice around big milestones - after the launch of a product, feature or program, on a quarterly or bi-annual basis, when there’s a major outage or failure. Truth is, I’m lukewarm about post-mortems. On the emotional spectrum, it feels good to air what went wrong and talk about what we could have done differently. But I’ve rarely seen learning pulled forward nor processes change as a result of the grievances. “Post” is too late in my experience to take action and to improve, but perhaps if I worked in an environment with more investment in operational excellence and a solid PgM (program management) team I’d have a different report.

Despite my critique, I do find post-mortems positive for morale, to ensure the team is heard and to help shine a light on human dynamics, where there is often room for growth. In such cases, visibility is the first step towards accountability.

A more optimal moment to talk about death

Then there’s the pre-mortem. I haven’t seen a product team host a pre-mortem prior to launch, but I think it would be a powerful tool to help anticipate, forecast, define success, while managing results. PM leaders like Shreyas Doshi have found great value in a modified version of Gary Klein’s original pre-mortem which Doshi says “enabled ‘calm product launches’ and have enhanced team productivity and morale.” Much like how corporate culture has turned death into a sunset, Shreyas found that through changing the pre-mortem language, the team was more psychologically safe in the activity.

🐯 Tigers - A clear threat that will hurt us if we don’t do something about it.

📃 Paper Tigers - An ostensible threat that you are personally not worried about (but others might be).

🐘 Elephants - The thing that you’re concerned the team is not talking about.

[Take a look at the Stripe blog to leverage Shreyas’ pre-mortem template].

While working on the Founders in Residence program in Area 120, my design partner Chris Gaffey and I decided we needed to surface stakeholder expectations and understand how to drive alignment earlier. We introduced pre-mortems prior to launching research. Our adaptation of the exercise opened a door that hadn’t previously existed, an unvarnished lens into the perception of research success. It helped us and the researchers prioritize what was most critical to include in the plan and to address any gaps in UX understanding. For the workflow, I think a research pre-mortem belongs after a research kick-off, but before the research plan is written.

[A snapshot of the research pre-mortem. If you want a PDF with further directions, please subscribe if you aren’t already and reach out to me].

A practice that could help us strategically prepare for or perhaps avoid death with an alternative trajectory

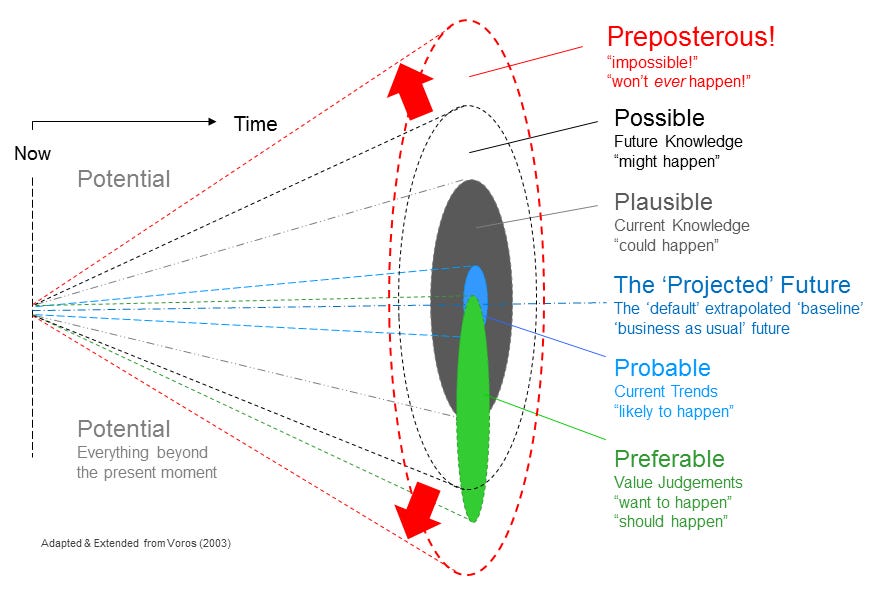

Futurists talk about three trajectories: possible, probable, and preferable. Charles Taylor first came up with a futures cone in 1990, and since then it has been iterated time and time again. My favorite rendition is by Joseph Voros who expanded the classes of futures in a way that sparks imagination and discussions we too often avoid when planning or deciding where to invest resources.

[Diagram credit: Joseph Voros]

While I introduced Futures at a high level to the Google Analytics team and attempted to expose the Area 120 org to the practice - it never quite stuck. Futures methods challenge what I call the ingredients of believing [ref: my and Barb’s post about assumptions], it’s a threat to business as usual that dismantles everything we think we know. Tech and product organizations should integrate possible futures and scenarios more readily into our repertoire. The challenge is how mired product organizations become to our vision, to our roadmap, to our strategy.

Our present and reactive nature inhibits us from more radical creativity and preparing for unexpected outcomes.

More eloquently put, Adam Elmaghraby a Strategic Foresight leader says “Futures guides product teams to unpack and balance the present demands of the business with what is happening in the market. Balancing these forces can hone the vision, how we approach strategy, and respond to disruptive forces in the market effectively - hopefully tempering the desire to become reactive.”

[I’ve created a simple 3 sheet workbook for all subscribers who want to dip their toes in Futures.]

Celebrating tech death and failure

Search “product eulogy/ies”, and besides “Killed by Google” and Steve Jobs’ funeral for Mac OS 9 in 2002 at WWDC, you won’t find much. Tech could learn something from the diverse cultural rituals around the end of life. Other than at X, I’ve never heard of sunset or failure celebrations that honor learning, impact and growth. In Area 120, we aspired to create a book end ritual and to even challenge the verbiage, but it never happened.

Ironically, the day before the layoffs I was co-facilitating a Generative Media workshop for the investment partners. One of the exercises we didn't get to was a Eulogy for the organization. This idea came from the sharp folks at SolveNext who trained me in Think Wrong about 5 years ago. The Eulogy is one of their many brilliant and tangible exercises.

Writing a eulogy was cathartic. But after the fact, I realize that a eulogy really should be written prior to death because it’s a planning tool that prompts self-reflection and could pave the road for iteration or a pivot. Voice also changes post-sunset, when you are in a state of mourning. Evidently, The NY Times journalists have a whole archive of pre-written obituaries for the living greats. It sounds dark, but they need to be prepared. A eulogy requires research, nuance, and it’s easier to write when the subject, whether human, object or code is living.

My Eulogy for Area 120, a special piece of Google.

Area 120, you were vibrant. A haven for bottom-up innovation. You were a place that beckoned Googlers with bright ideas, a passion for making, and a relentless entrepreneurial spirit. For those who found a home in you, it was more than just an incubator; it was a magnet for creativity, a neutral ground where ideas flourished and teams thrived.

Area 120 you were more than a place; you were a state of mind.

Hundreds of Google's most talented joined with conviction and vision. In Area 120 they could learn, experiment, create, and collaborate at breakneck speeds. Often, making the impossible possible was a reality through grit, determination, and sheer force of will.

You weren’t perfect either. Like other corporate innovation hubs you struggled with your identity - to balance empowering Googlers while meeting company-wide objectives, to inspire transformational and later adjacent products while staying on brand, to solve real market problems while achieving Google scale. Like any organization, you evolved under new leadership, but your ethos never changed. There were multiple Area 120 eras, different philosophies, structural changes, new goal posts, yet each was beautiful and challenged the status quo in unique ways.

Under the banner of Area 120, Google incubated over 180+ products, ranging from creator economy tools to privacy-first solutions to enterprise collaboration platforms. With 30+ of these product teams acquired by Google, we can proudly say that our work has left a lasting impact on the company and culture. Not only did Area 120 foster innovation within Google, but its products also impacted the world beyond. From making the corpus of creator content widely accessible to ensuring mobile apps are compliant with privacy regulations, the impact of Area 120 is felt far and wide.

Area 120 may be gone, but we Area 120 Xooglers will continue to make our mark. Let us carry that legacy forward and continue to solve real problems, to experiment, and to create.

Area 120, we will miss you. Thank you for all that you were.

Call to action

We all know the jockey vs. horse analogy is an overly simplistic dichotomy that doesn’t reflect the dimensions of startup endings (aka failure). Help us collect data! If you are a founder of a shut down startup fill out this survey about endings. If you aren’t a founder, but know one, pass the link along. We will share the results and analysis on Substack once we have enough responses.

https://forms.gle/Hhv2XfkEKsXjSkrV7

Thinking about failure is a great way to help identify hidden risks early!